Which Planets Sound Good to Live On?

Let’s go through them.

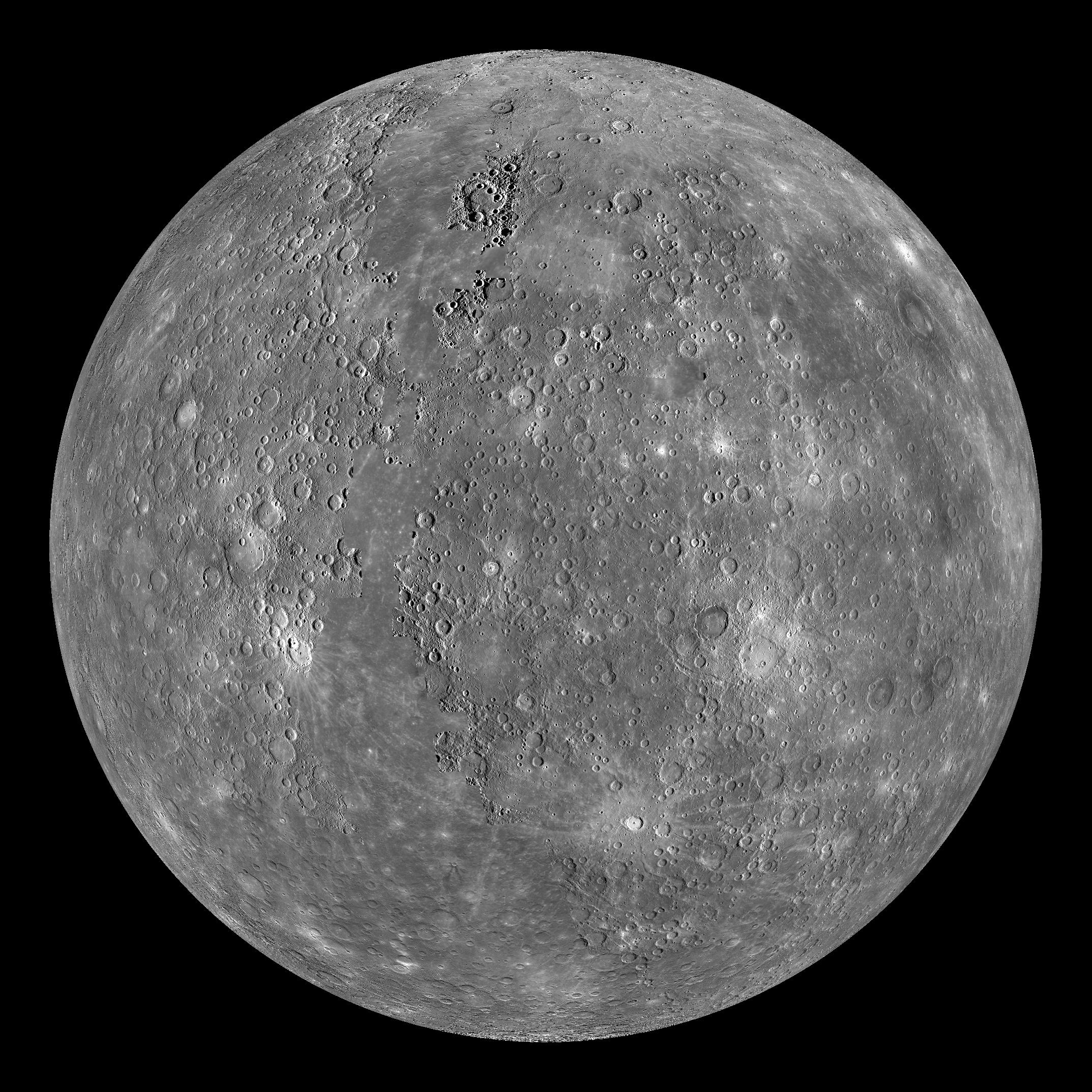

Mercury

Mercury had the bad luck of being the closest planet to the sun, which is like being seated at a table next to a 450-pound, aggressively upset man. And if you were on Mercury, your day would be spent in 800 F (430 C) weather—so hot that you could put a chunk of lead on the ground and it would melt into a puddle. There’s almost no atmosphere on Mercury, so while you were burning to death, you’d also be standing in a near vacuum, which would rip the air immediately out of your lungs and begin to vaporize the moisture in your skin. The lack of atmosphere would also mean you’d be badly poisoned by radiation from the sun (which would look 2.5 times bigger in the sky than it does on Earth). On the plus side, Mercury’s gravity is only 38% of Earth’s, so you could jump around in a silly way as you died instantly. At this point, you’d be highly anxious for nighttime to arrive, and you’d be unhappy to learn that a Mercury day/night cycle is 58 Earth days long.

A month later, when night finally arrived, you’d be in the best mood ever for a minute before you realized that now it’s -280 F (-170 C), which is 152º F colder than the coldest recorded temperature in Earth’s history (Vostok Station, Antarctica). This is because there’s no atmosphere to trap any of the sun’s heat or distribute it around the planet. You’d also still inconveniently be standing in a vacuum. You’d have to spend a whole month deeply frozen to death before you could finally burn to death again upon sunrise.

Your best bet on Mercury would be near the poles which, while freezing and eternally dark, at least have ice on them so you could keep hydrated. In theory, a human base could be built near there, but the upside would be small.

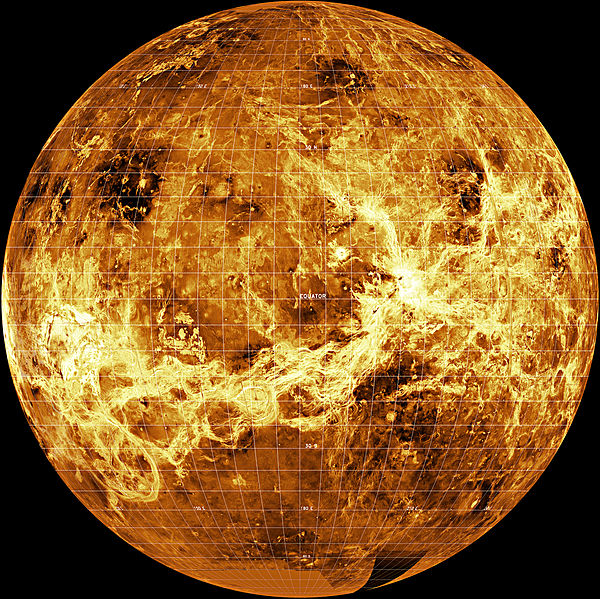

Venus

Venus, not to be outdone in terribleness, manages to make living on Mercury sound like sitting on the beach in Maui eating a grilled shrimp.

It turns out that a vacuum is a lovely place to be compared to the exact opposite situation Venus has going—an incredibly dense atmosphere. Here’s how a Venus visit would go:

First, the air is 96% CO2 and poison to breathe.

Second, who cares about the air’s breathability when you’d be immediately flattened by the atmosphere, which would weigh down on you with more than 90 times the Earth’s surface air pressure. The pressure would be the same as you’d feel if you were 1 km under the ocean—three times deeper than the scuba diving record depth. If you somehow could stay upright, the air resistance would be so strong that moving your arm would feel like moving it through water.

Third, who cares about either the first and second thing because it’s 870 degrees Fahrenheit (465 C). Imagine heating up an oven so blazingly hot that it melts lead, then heating it up another 138 degrees—and then making that the temperature of the entire planet. At night (which again takes a while—Venus’s day is longer than its year4), Venus’s temperature stays exactly the same because the thick atmosphere traps the heat inside.

During the day, you’d experience all of this in dim light, under a reddish-orange cloud cover. The sun would only be seen as a hazy, brighter, yellower part of the sky. At night, you’d live in utter starless blackness—all while being flattened in a sizzling furnace. At least there wouldn’t be any bugs.

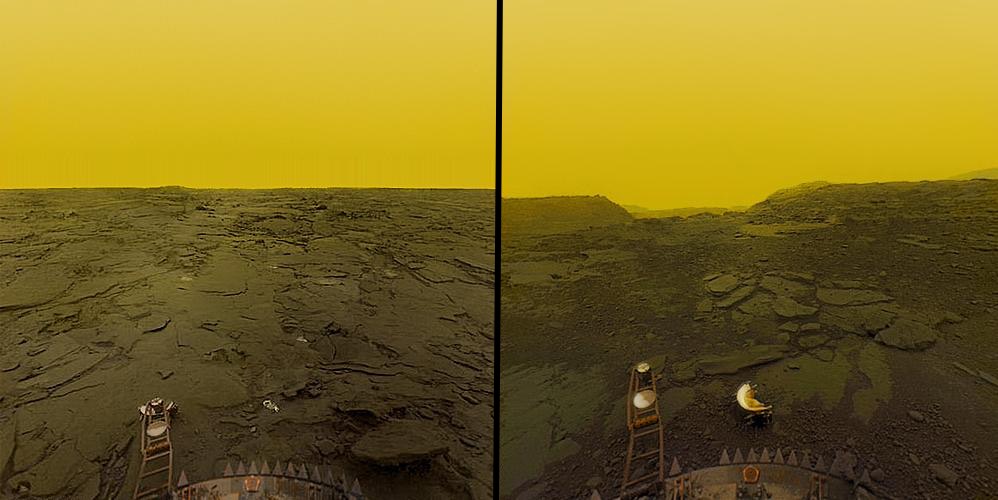

Given everything I just said, I’m super impressed with the super-tough lander of Soviet probe Venera 13 that descended all the way to the surface of Venus in 1982 and managed to stay alive for 127 minutes—long enough to snap these two photos, the only images we have of Venus’s surface:

Wind is one problem you don’t have on Venus’s surface, where you’d only feel a light breeze—but as you ascended up through the atmosphere, that would quickly change. The upper atmosphere of Venus is a new kind of trouble—constant winds double the speed of our most powerful hurricanes, and droplets of sulfuric acid (the same acid used to unclog drains) everywhere, whizzing into your face. Typical Venus.

Curiously, though, if you got all the way to the top of Venus’s miserable atmosphere, you’d be rewarded with—shockingly—pleasant, livable conditions. Randomly, at the top of Venus’s clouds is a layer where the temperature and pressure are similar to those on Earth, and because oxygen and nitrogen both rise in Venus’s dense atmosphere (like helium does on Earth), the air in that layer might actually be close to breathable. That’s led some scientists to actually discuss human colonization of Venus’s high atmosphere, building “cities designed to float at about fifty kilometer altitude in the atmosphere of Venus.”

When I asked Musk about Venus, I was surprised to hear him actually suggest that the planet could be made livable “with extreme difficulty.” He says that way down the road, with advanced enough technology, there could be ways to clear out most of Venus’s atmosphere and possibly make it a far-future option for colonization.

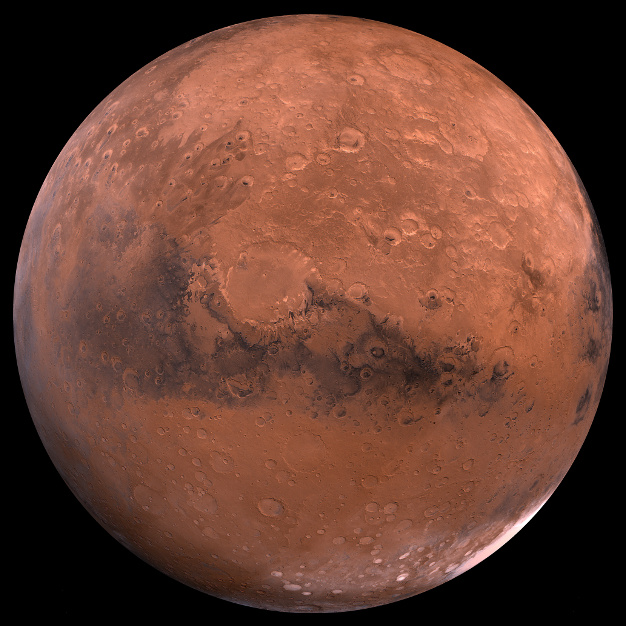

Mars

If Mars were a place on Earth, no one would ever want to go there. But in a discussion of inhabiting non-Earth planets, all of which are a total nightmare to live on, the prospect of moving to Mars sounds oddly okay.

Mars is basically a colder Antarctica that looks like the Arizona desert with air you can’t breathe and a sun that radiates you to death if you’re exposed to it for long. Every part of Mars is dramatically less livable than the least livable place on Earth. But the conditions are reasonable enough that with a man-made “hab” to live in, a little greenhouse garden, and a good enough spacesuit, you could actually exist on Mars without dying. There’s even water on Mars—lots of it—tied up in ice on the poles, and if you’re in the right part of the planet at the right time of year, you can enjoy glorious 70 F (21 C) weather. Or you can at least know that it’s nice out while you’re looking out the window of the hab.

A Mars day (a “sol”) is about 24.5 hours, which would work nicely for both humans and plants. And with 38% the gravity of Earth, you could kind of function normally. There would be some fun low-gravity perks, like being able to dunk on a 15-ft hoop or living on the second story of an apartment building and leaving for work in the morning by jumping out the window (roughly 1/3 the gravity means that whatever jumping from an X-foot ledge would feel like on Earth would equal the impact of jumping from a 3X-foot ledge on Mars.)

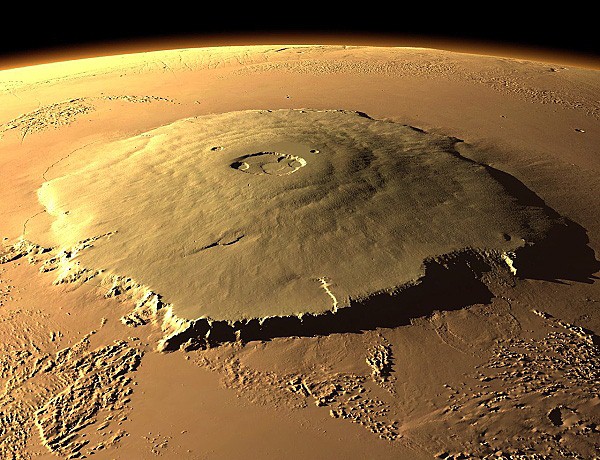

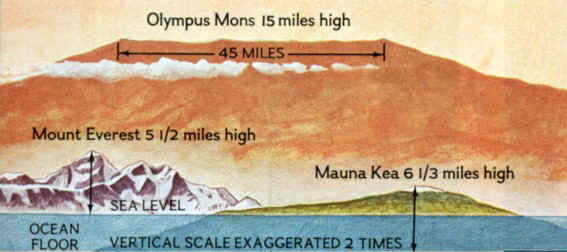

The coolest tourist attraction in the Solar System is also on Mars—the Solar System’s tallest mountain, Olympus Mons

Which would cover Arizona and makes Everest look like a foothill

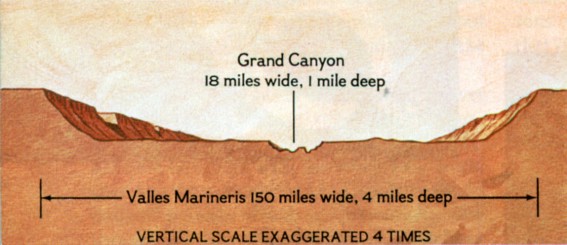

Not to mention Mars’ canyon that makes the Grand Canyon look like a paper cut

We’ll get into this more later, but in theory, with enough effort and technology, humans could terraform Mars and sometime down the road have a somewhat pleasant planet to live on, with trees and oceans and no need to wear a spacesuit outside.

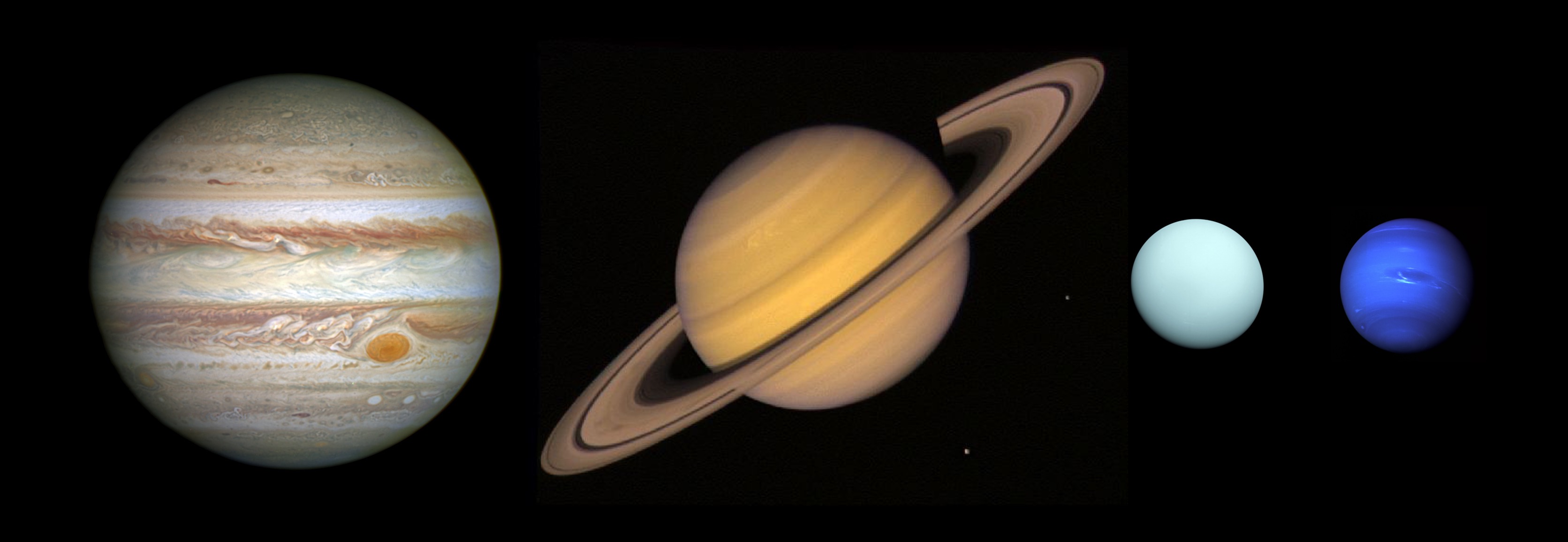

Jupiter and Saturn and Uranus and Neptune

I hope you’ve enjoyed floors, because none of the other planets have one. Here’s how the four faraway planets ended up being so weird:

4.6 billion years ago, there was a huge cloud of gas existing in space when some perturbation triggered the process of it condensing on itself. The universe’s matter knows full well what that means—it’s suddenly Black Friday and it’s a frantic race to scoop up as much of the matter as possible. As every star and planet will tell you, the key is to get the lead early. If you start off with the most mass, you’ll have an easier time collecting more and becoming even bigger, further increasing your advantage. Once there’s a clear early leader, they’re hard to catch.

The eventual winner gets to become a star—everyone else will end up as gawking paparazzi planets revolving around the star for 10 billion years until finally the star becomes washed up and retires and then a new game starts.

In the case of our Solar System, the sun pulled out the victory, scooping up about 99.8% of the gas cloud’s total matter in the process. At that point, it becomes a bloody battle over the remaining scraps. Those who can gather enough will at least have the dignity of being a planet. Those who try and fail will end up suffering the shame of spending 10 billion years as a planet’s paparazzi—a lowly moon.

The hapless matter who manages to fail to become a star, planet, or a moon will be doomed to become either an asteroid—the Solar System’s homeless man—or be absorbed into a larger body and lose their identity altogether. It’s a tough world out there.

During this rat race, an awkward thing can happen. Sometimes there’s certain matter not experienced enough to know the golden rule of solar system formation—know when you’re beat. Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars clearly read the signs early, could see that the sun had too big a lead, hung up the acting career and moved on. They switched gears and started working on becoming a planet.

The four gas giants, on the other hand, continued on in vain, collecting gas in a sad and desperate attempt to turn the tables. And when you do that, you end up in a bad situation—as a bizarre “almost-but-not-quite-star.” Jupiter’s composition is hydrogen and helium, just like the sun, but unlike the sun, Jupiter doesn’t have enough mass to ignite fusion, only enough to forever remind everyone of its failed attempt at stardom.

The gas giants won’t admit it, of course. Once it became entirely clear that they would not become stars, all four of them quickly changed their tune, pretending they had been trying to become planets all along. Now they’re left in a depressing no-man’s land between star and normal planet and will spend 10 billion years as bloated planets with no surface. No one wants to be a planet with no surface.

We’re not sure exactly what goes on inside of a gas giant like Jupiter. If you tried to go find out, you’d zoom down through the outer clouds as the strong gravity (2.5x Earth’s gravity) pulled you in faster and faster. As you fell, things would get darker, hotter, and the pressure would grow higher and higher. Eventually, you’d be in the pitch black, the temperature would exceed the temperature of the sun’s surface, and with a massive amount of atmosphere above you, the gas around you would be so pressurized that you wouldn’t be able to distinguish it from a liquid (this is called a “supercritical” state). The hydrogen would then become so condensed that electrons would begin to flow from atom to atom, turning it into a liquidy sea of electricity-conducting metallic hydrogen. Whether at the very center of Jupiter you arrive at a solid core is up for debate.

What’s not up for debate is that humans will never move to Jupiter. Or Saturn. Or Uranus. Or Neptune.

Where humans could possibly move to are the large, rocky, ice-covered moons around Jupiter and Saturn. But it wouldn’t be warm. We could maybe move to our own moon, but it’s just a milder version of the Mercury situation—daytime temperatures that can boil water into gas, nighttime temperatures that can condense oxygen into liquid, and no protection from the sun’s radiation. And the 28-day rotational cycle means plants need to endure two weeks at a time in the dark—not easy.

When I asked Elon Musk about where other than Mars humans could potentially move to, he said there were a handful of places that could work if our technology becomes advanced enough—several moons, a few of the largest asteroids, even Mercury and Venus if you really want to get crazy, but he finished by saying, “I mean, Mars is by far the best option.”

Before we go back to the non-blue world of the normal post, can we just acknowledge how good living on Earth sounds right now?? Imagine the privilege of living in room temperature weather, one atmosphere of pressure, g gravity, light breezes, watery rainstorms, plentiful liquid oceans, magnetic and atmospheric protection from the sun, food everywhere, and air you can just breathe in. You need a huge number of different conditions to be precisely correct in order for you to be able to just stroll around outdoors without a spacesuit. So let’s all appreciate the luxury of living on Earth for the next seven minutes until we all simultaneously forget to give a hoot about it again.

This has been reproduced from the “Wait But Why” blog post about SpaceX’s plans to establish a human colony on mars, it is an extremely interesting article, containing the following as an aside. It has been edited for continuity and a middle school audience.