his has been reproduced from the “Wait But Why” blog post about SpaceX’s plans to establish a human colony on mars, it is an extremely interesting article, containing the following as an aside. It has been edited for continuity and a younger audiance.

What is an orbit?

It’s intuitive to think that the challenge of putting an object in orbit is the difficulty of getting it up to orbit, just like it’s intuitive to think that the astronauts in the ISS are floating around because there’s no gravity up in space where they are. This is a good time to stop trusting your intuition.

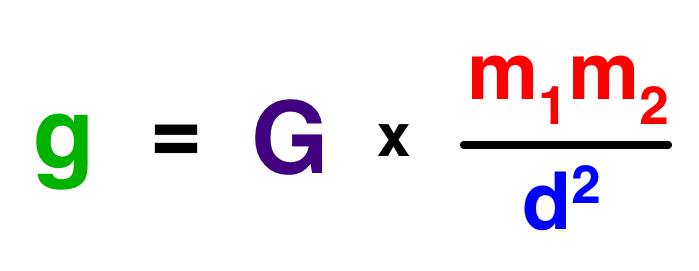

Let’s zip back to high school for a second. Here’s the equation we use to figure out the force of gravity:

G is the gravitational constant, a super-icky number we can ignore for this exercise.

m1 and m2 are the masses of the two objects. There are two objects because gravity isn’t a one-way thing—every two objects attract each other with an equal force. In the case of you and the Earth, what you think of as your weight is the force of gravity between you and the Earth, a force acting equally on you and the planet. And because the two mass numbers are in the numerator, it means that when they go up, the force of gravity will go up too (proportional to their product). So if I doubled your mass, your weight would double. If I left your mass the same but doubled the Earth’s mass—again, your weight would double. If I doubled both your and the Earth’s mass—your weight would quadruple. For our purposes in this post, we don’t need to work with mass.

What we care about is the d2 part. d is the distance between the two objects—or more specifically, the distance between the centers of mass of the two objects. In the case of the Earth, the mass is symmetrically distributed, so the center of mass is the center of the planet. The Earth’s radius is 3,959 miles (6,371 km), so when you’re on the surface of the Earth, that’s the number you use for d to determine the force of gravity you’re experiencing. Because d is in the denominator of the equation, as d grows, the force of gravity decreases.

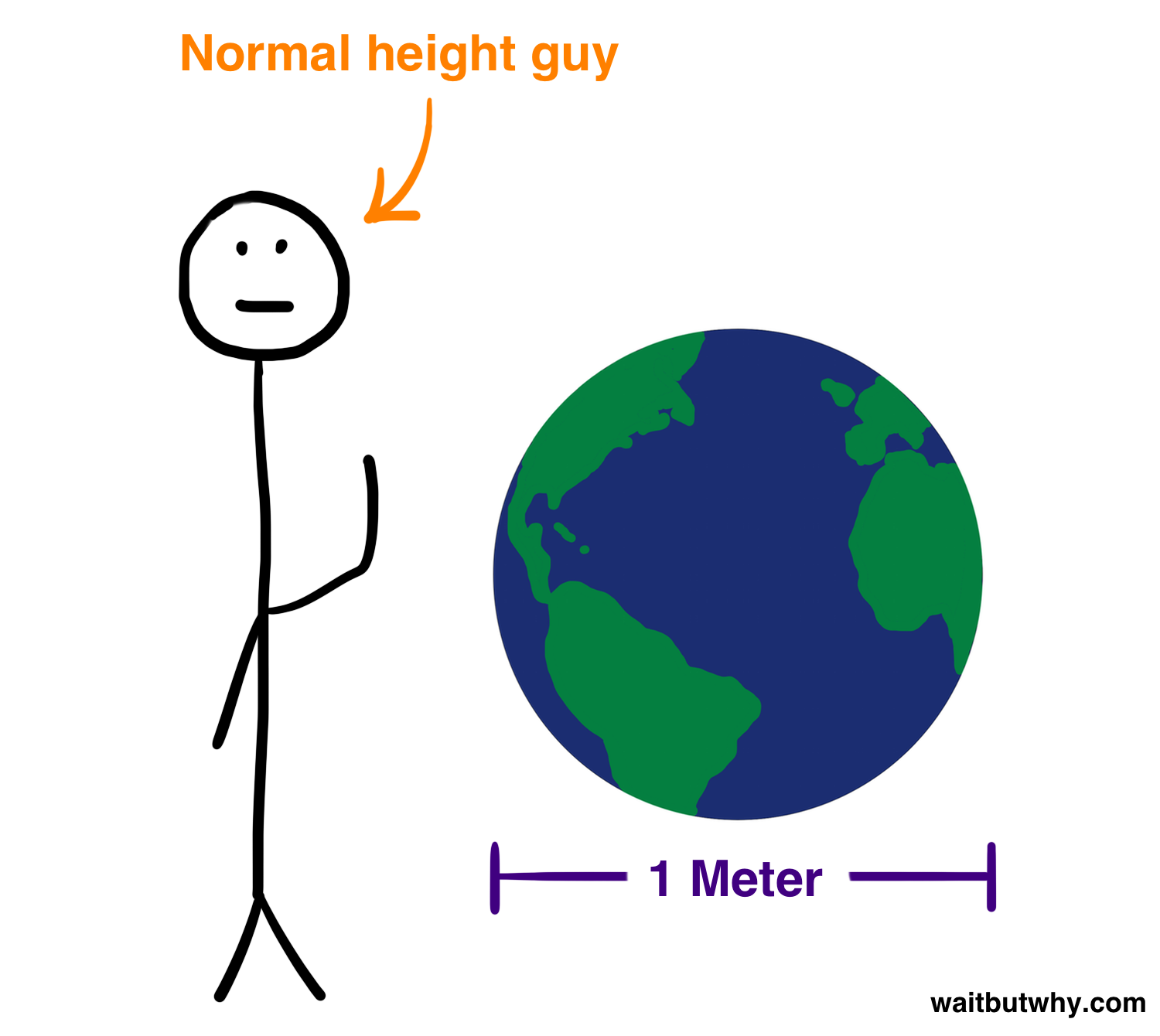

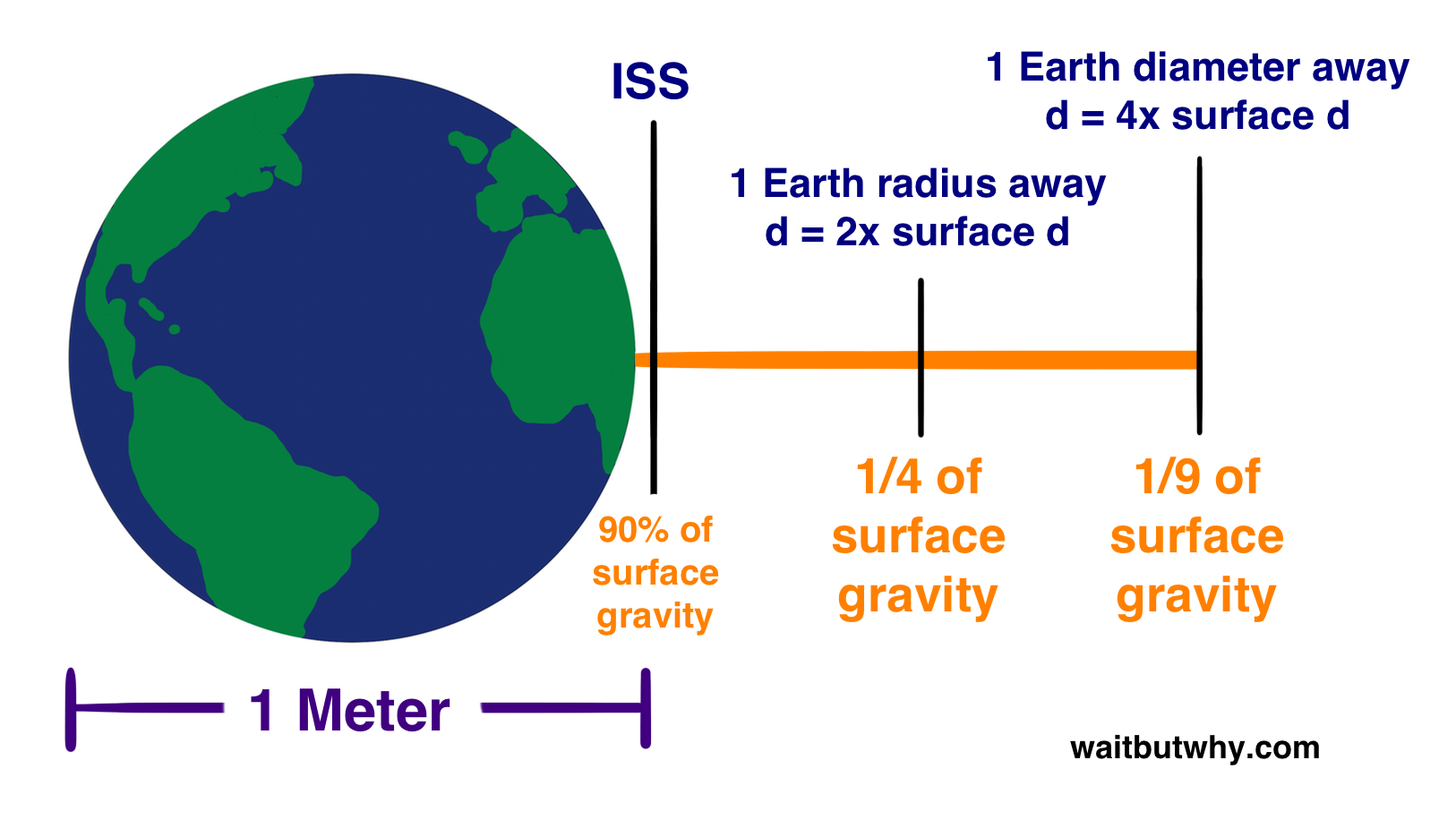

To illustrate all this, I’m going to shrink the Earth down to about one 13-millionth of its size, so that it’s exactly one meter in diameter:

If we double d by moving an Earth radius away from the surface (half a meter), d2 goes up by 4x, so the force of gravity, and your weight, would be a quarter of what they are on the surface. If you moved to a full meter away—where you could fit a full Earth between you and the Earth—d has now tripled and your gravity is 1/9 of what it is on Earth.9

And where does the ISS fall in all of this?

It’s between 205 and 255 miles away, which on our meter globe is about 2-3 cm, or a little over an inch from the surface. If a ping pong ball were stuck to the globe, the ISS (and a lot of satellites) would run into it. (While we’re here, the commonly-recognized altitude where “space” starts is the Kármán line, 62 mi (100 km) up, which on our globe starts 7.8 mm above the surface—about the width of a pencil. And an airplane flies at .84 mm off the surface, about the height of a grain of sand.)

So what does that mean about gravity in Low Earth Orbit, in a place like the ISS?

Well if we take the mid-point of the average altitude of the ISS (230 mi), we find that being at that height adds only 5.8% to the normal d on Earth’s surface, which only brings surface gravity down by about 10%.

So ISS astronauts should barely feel the gravity difference. And yet, they’re floating.

The reason is they’re in free fall.

I once had a chance to fly in a little plane with a pilot who didn’t care, so he brought the plane up to 4,000 feet and then quickly dropped to 2,000 feet. Before the drop, he handed me a pen and told me to rest it on my open palm. During the drop, the 8% of me not in bed-wetting survival mode saw the pen hover in front of me and gently float over to the side before abruptly dropping into my lap when we leveled off again at 2,000 feet. This is what’s happening inside the ISS at all times.

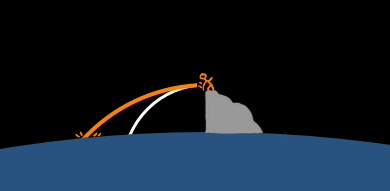

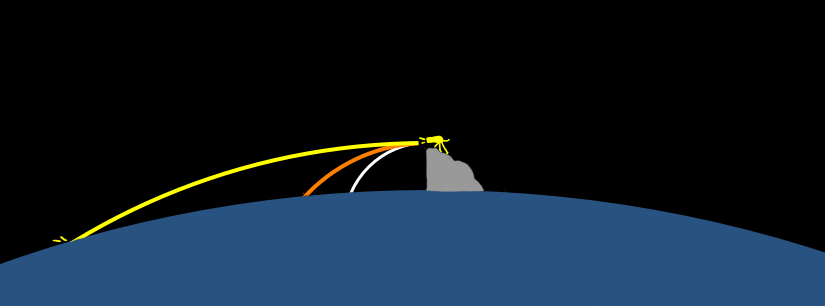

Here’s why: picture you’re standing on a cliff on a planet smaller and smoother than the Earth and with no atmosphere—and you throw a baseball as hard as you can.

It would go something like this:

Now what if a major league pitcher gave it a try. It might look like this:

And what if you fired the ball out of a cannon? It would go even further.

Before each of these balls hits the ground, they fly in a curved path. If the Earth’s surface didn’t get in the way, those paths would continue as long ellipses. To keep things simple, let’s just match each path up with a circle whose curve lines up with it ball’s trajectory pretty well:

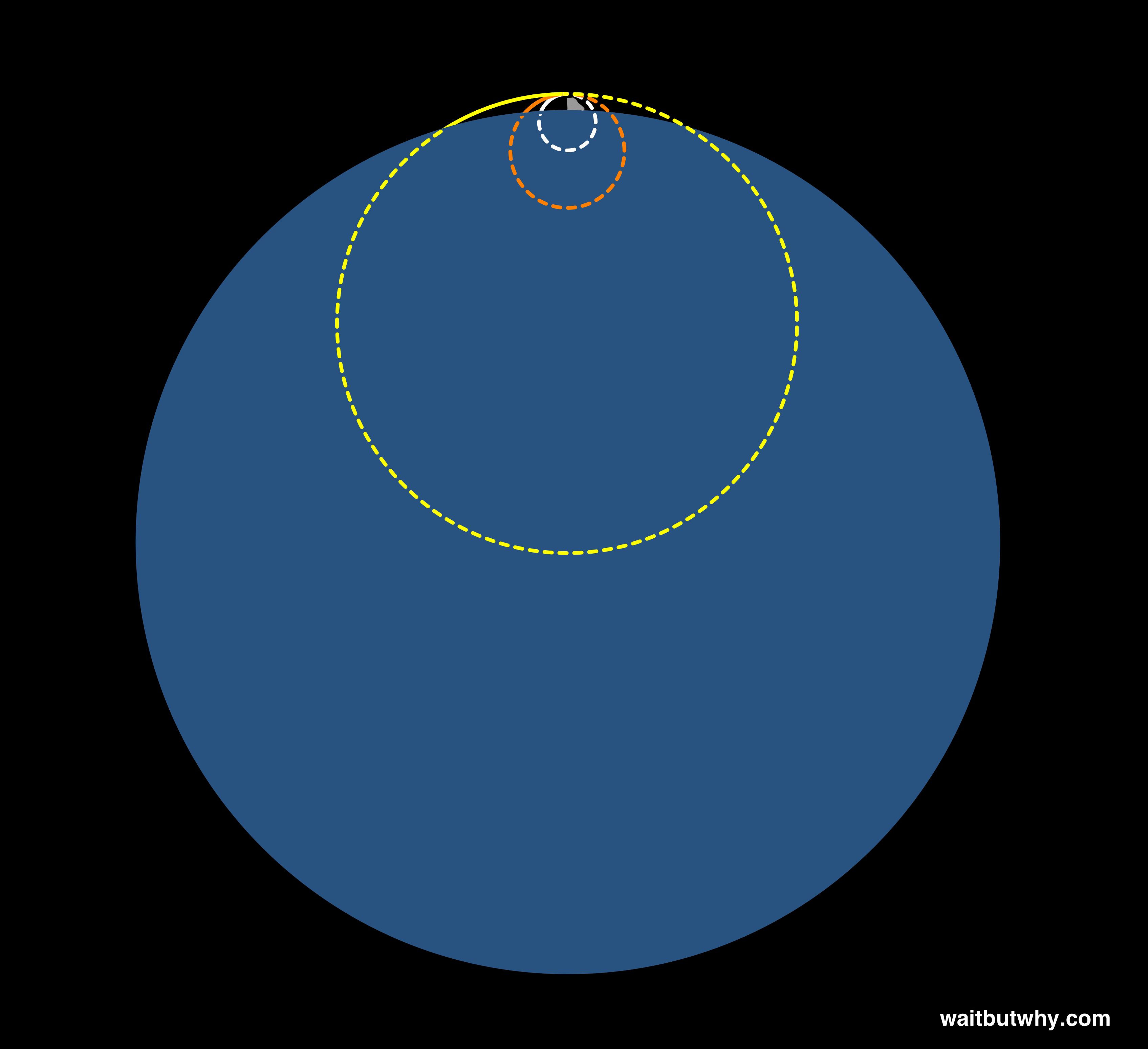

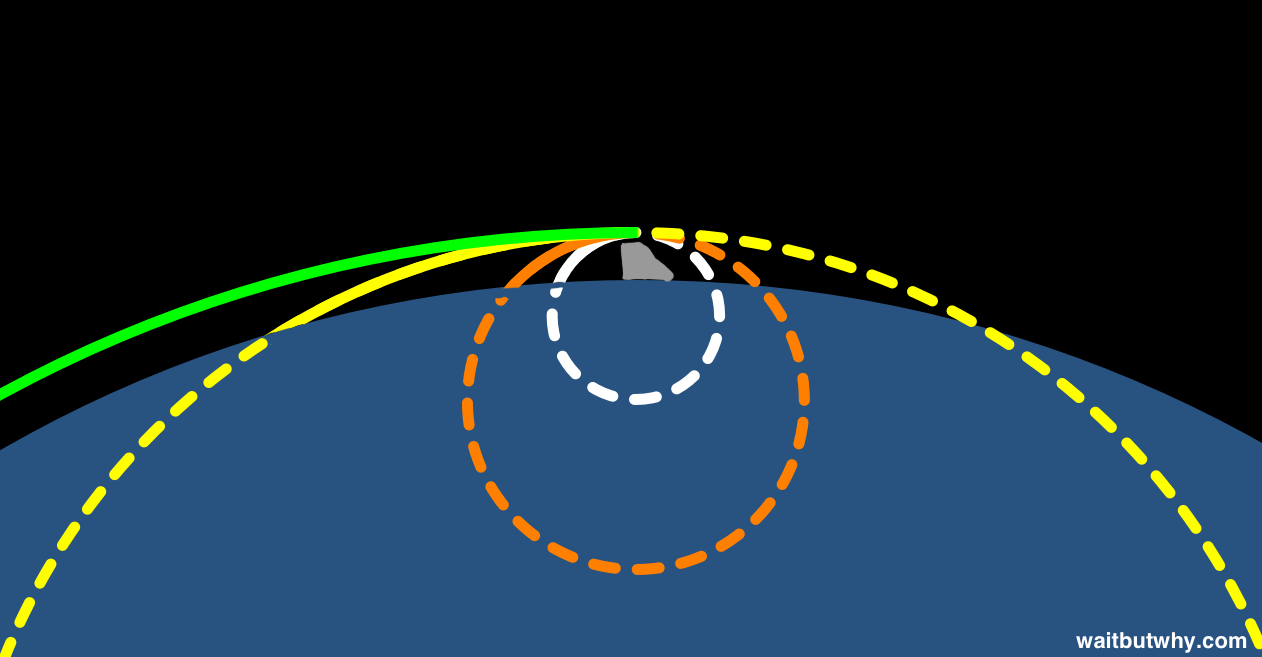

Now let’s get a much more powerful cannon, and it does this:

Seems normal, but notice that the arc’s curve is matching the shape of the planet. So what ends up happening is this:

The ball would circle the planet and run into the back of the cannon. And if nothing were there to block it, the ball would continue “falling” forever, never able to land. Because the ball’s path’s curve, and corresponding circle, match up exactly with the curvature of the planet, the planet keeps falling away from the ball as the ball tries to fall down to the ground. You’ve put the ball in orbit.

If you had a perfectly smooth planet of any size, and it had no atmosphere at all, you could in theory put something into orbit right above the ground. But because the Earth has a thick atmosphere (and an uneven surface with mountains), no matter how hard you fired a ball near the surface, the atmosphere would slow it down, making its path’s curvature tighter and tighter until it fell out of orbit and hit the ground. That’s why everything we put in orbit is high up, where the atmosphere is so thin it doesn’t slow the object down. And without any force of friction to interfere, Newton’s Law of Inertia kicks in and it’ll circle the planet forever.10

In order to fall into orbit around the Earth, an object has to be moving unbelievably fast. But not too fast. Why? Because then the curve is too broad, the corresponding circle is bigger than the planet, and this happens:

That’s why people talk about something reaching “orbital velocity” to stay in orbit, and “escape velocity” to escape from the Earth’s gravity well and head out into space. Escape velocity just means the arc the path makes is broader than the curvature of the planet.

So what’s orbital velocity at about a 230 mi altitude where the ISS is? 17,150 mph (27,600 km/h). Or 4.76 mi / 7.66 km per second. That’s the goldilocks speed that will keep an object in orbit at that height.

To get a feel for how fast that is, if you threw a ball at that speed from the beach into the ocean, it would zing out and over the horizon, out of sight, in about a half a second. At that speed, the ISS circles the Earth every 90 minutes (and yet, because velocity is relative, the astronauts in the ISS don’t feel like they’re moving at all, the same way you don’t on an airplane).